Introduction

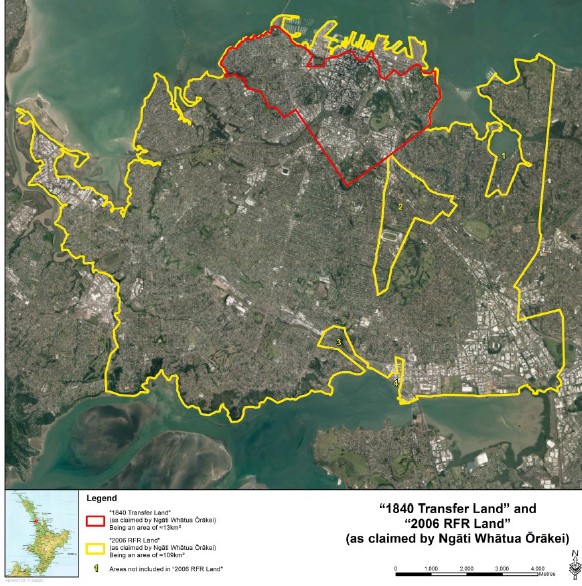

Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Trust v Attorney General (No 4) [2022] NZHC 843 is a 288-page High Court decision in which Palmer J declined an application by Ngāti Whātua seeking a declaration that, under tikanga, Ngāti Whātua has exclusive “ahi kā” and “mana whenua” over central Auckland (the area over which the declaration is sought is the feature image for this post). What “mana whenua” and “ahi kā” mean are unclear, but it appears that the application, if granted, would have confirmed that Ngāti Whātua had exclusive rights and effectively extinguished other groups’ interests. So, the Crown and other iwi opposed the declaration sought.

After a 37-day trial, Palmer J declined to make the declarations Ngāti Whātua sought but invited further submissions on several issues. Many aspects of Palmer J’s judgment merit comment, but the short take away is that it is discusses tikanga in depth. It also enters into controversial territory.

What is tikanga?

Parliament has previously defined tikanga in legislation. As an example, section 2 of the Resource Management Act 1991 defines “Tikanga Māori” as “Māori customary values and practices”. Other statues also provide similar definitions of Tikanga as a customary practice.

In his judgment Palmer J answers “what is tikanga?” at paragraphs [298] to [317]. Notably, Palmer J does not refer to previously decided case law, or any of the definitions of tikanga contained in legislation, at this point. Instead, after reviewing the evidence put before him Palmer J says “tikanga can be viewed as consisting of norms of behaviour which a hapū or iwi develop over time and which acquire such force that they are regarded by that hapū or iwi as binding” (at [305]).

Tikanga explained simply

Palmer J is effectively saying is that tikanga is a system of rules that governs conduct. But, as the judgment makes clear, there is more to tikanga. Palmer J cites evidence that tikanga has its origins with Māori gods which “gives it validity and tapu sanctity”.

Furthermore, Palmer J found that Tikanga:

- Comprises of principles (at [306]). Palmer J adopted a submission by counsel that Tikanga is a “system comprised of interwoven principles that guides action and relationships” (at [306]). However, what these principles are is unclear and debated. There are different versions of which principles are “core” to tikanga. Additionally, the relevant principles of tikanga will depend on the context of each issue that arises (at [311]).

- Revolves around values (at [307]). Palmer J cited a report of the Law Commission from 2001 which stated that “Tikanga Māori comprises a spectrum with values at one end and rules at the other, but with values informing the whole range. It includes the values themselves and does not differentiate between sanction-backed laws and advice concerning non-sanctioned customs. In tikanga Māori, the real challenge is to understand the values because it is these values which provide the primary guide to behaviour” (at [307]).

- Is fundamental to “constituting” an “iwi” or “hapū” (at [310]). Palmer J says of iwi and hapū that tikanga “is essential to their identity … Without their tikanga, an iwi or hapū are not who they are” (at [310]; and [30]).

- Is developed by each iwi and hapū (at [310]). This appears to mean that for every iwi there will be differences in their tikanga. Further, Palmer J says: “Iwi and hapū create, determine and change tikanga through their own deliberative aggregation of practices …”.

- Changes over time as circumstances change (at [312]). (For example, litigation is now the modern alternative to resolution by battle which used to be, but is no longer, available to break a deadlock over tikanga (at [368]).

- Loses something when reduced to writing (at [317]). Palmer J said that “tikanga loses something when reduced to writing. It even loses something when explained orally, in the abstract. Tikanga is performed, more than stated. This is relevant to the giving of evidence of tikanga in court. The tikanga experts who gave evidence at trial were impressive in their command of nuance and subtlety in identifying and distinguishing how relevant principles of tikanga apply to different contexts. But their explanations and examples do not simply involve the dry stating of a principle and outcome. Sometimes, more meaning lies in what is not said. The invoke unstated but salient human characteristics and virtues, such as honour, humility, and humour. Oral evidence of this is important. A written record is inferior. …” ([at 317]).

On this last bullet point, the judgment records that many experts in tikanga were uncomfortable with tikanga coming before the Court. One counsel cited a statement by then Chief Justice Williams of the Māori Land Court that “Tikanga divined by a judge who is not a member of the kin group and handed down from on high … would be the antithesis of Tikanga”.

Is tikanga law?

The New Zealand Supreme Court considered the legal status of tikanga in Trans-Tasman Resources Ltd v Taranaki-Whanganui Conservation Board [2021] NZSC 127 (an appeal relating to a permit to mine iron sands). The majority reasoned that tikanga is a body of Māori customs and practices, part of which is properly described as custom law, and required the decision maker to have regard to aspects of tikanga as “applicable law” under the relevant legislation.

However, Williams J (formerly Chief Justice Williams of the Māori Land Court) went further than the other judges. He broadly agreed with the conclusion that tikanga was applicable law under the relevant legislation, but he then said that “As to what is meant by “existing interests” and “other applicable law”, I would merely add that this question must not only be viewed through a Pākehā lens”. Williams J then said that the Māori values “are principles of law that predate the arrival of the common law in 1840” (see [297]).

Following on from Williams J’s lead, Palmer J has now said that tikanga was New Zealand’s “first law” and that it accompanied and governed Māori when they arrived (see [326]). Palmer J then concludes tikanga “can be conceived of as a sphere of law in its own right”.

What is the test for law?

Many thousands of litres of ink have been spilt debating the meaning of “law”. No definition of law is perfect, because the meaning of law is both context specific and flexible. The word “law” can apply to many different systems of social organisation that regulate power/behaviour.

Traditional definitions tend to think of law as universal and knowable in advance. Further, law has long been associated with the written word (since at least the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi dated to ~1754 BC). But, in theoretical jurisprudence (at least) the absence of writing is not necessarily considered an insurmountable obstacle to existence of law. Law is not to be equated with statutes, civil/criminal procedure, and decisions of courts – although each of these is a fundamental feature of the common law.

Despite the difficulty there is a recognised and conventional corpus of jurisprudence which attempts the task of defining law. John Austin (1798-1859) defined law as a system of commands and sanctions from political superiors to political inferiors. For Hans Kelsen (1881-1973) law was a certain system or organisation of power tracing back to a basic norm (the grundnorm). For HLA Hart (1907-92) law is a system of rules the validity of which are determined in accordance with a rule of recognition.

In his judgment Palmer J does not cite or consider any of the above definitions. Rather, Palmer J cites the great legal philosopher Joseph Raz (1939 – 2022). Palmer J notes that Raz described “law” as “regulating human behaviour by prescribing conduct, and it expresses the decision to regard legal systems as independent normative systems”. Palmer J says tikanga provides rules, values, principles, and processes for identifying or developing customary practices, regulating behaviour, and resolving disputes.

But, as HLA Hart said when discussing the elements of law in his work The Concept of Law (1961), it is possible that “the rules by which [a] group lives will not form a system but will simply be a set of separate standards without any identifying or common mark except of course that they are rules which a particular group of human beings accepts”. Hart suggests that such a system would more closely resemble rules of etiquette than actual law.

If tikanga comprises of principles, revolves around values, is fundamental to “constituting” an “iwi” or “hapū”, loses something when reduced to writing, and that the antithesis of tikanga is having it divined by a judge who is not a member of the kin group, then it is doubtful that tikanga will fall within a traditional western definition of “law”.

Is tikanga a freestanding source of law?

By way of further background, Palmer J’s reasoning on this point includes that:

- Tikanga was the only effective law in most parts of New Zealand in the 1840s. But, by an Act of the New Zealand Parliament in 1858, the English common law as at 14 January 1840 came to apply to New Zealand – particularly after the wars of the 1860s (at [329]).

- The common law has long recognised that customs may survive the acquisition of sovereignty by conquest – if the custom is reasonable, certain, of immemorial usage, and compatible with the Crown’s sovereignty (per The Case of Tanistry (1608) Davis 28, 80 ER 516 (KB)) (at [333]).

- Modern case law indicates there is now no doubt that New Zealand common law recognises Māori customary law, or Tikanga. But, in modern times, Parliament has taken the lead in that, by passing legislation (at [336]). Contemporary statutes invoke tikanga explicitly and not infrequently (at [338]).

On this issue the Crown submitted that:

Tikanga Māori is given expression in New Zealand’s law either through common law recognition (as an underlying value that informs the interpretation and development of law, or alternatively as a source of private rights and obligations) or through statute. In other words, tikanga does not operate as a free-standing source of law separate from the common law and statute with the effect of displacing or superseding the application of the common law and/or statute (at [352]).

The Crown’s submissions represent legal orthodoxy. However, on this issue Palmer J concludes:

Based on my review of the legal authorities and submissions above, I consider it is clear that the law that accompanied Māori to Aotearoa was constituted by tikanga. Many aspects of it are law in New Zealand now: Māori customary law, made by iwi and hapū, governing behaviour of iwi and hapū and those who belong to them. As such, it is a “free-standing” legal framework recognised by New Zealand law. It does not cease governing an iwi or hapū just because the courts or Parliament or even other iwi suggest otherwise (at [355]).

If anyone ever wanted to argue that different laws apply to people in New Zealand depending on their race – then the above paragraph would be useful for that purpose.

Is Parliament supreme?

Palmer J goes on to say that:

Tikanga is often assumed, recognised and referred to by New Zealand legislation. Like the common law made by courts, the legal effects of tikanga can be overridden by legislation. But even Parliament cannot change tikanga itself…

However, section 15(1) of the Constitution Act 1986 provides that the Parliament of New Zealand continues to have full power to make laws. This reflects the fundamental common law principle, that Parliament is Supreme.

In the common law system it is not possible to maintain both that tikanga is law, that is recognised in New Zealand, and that Parliament does not have the power to make or change tikanga – at least at “common law”. Another way of putting it is that, if courts can make declarations about tikanga (see [458]) then Parliament can legislate about tikanga.

It would, however, be another thing to say that Parliament cannot change tikanga if tikanga is understood as being something that is different from law (or equity) and more equivalent to morality. On that approach it does make sense to say that Parliament may pass legislation as it likes, but it cannot change tikanga. But it is difficult to see how tikanga can be both “law” and “beyond the law” (or beyond Parliamentary Supremacy) within the common law system.

Concluding comment

It was bold of Palmer J to issue a judgment declaring tikanga to be a “freestanding source of law”. Doing so raises constitutional issues and creates legal and political uncertainty. It is also difficult to reconcile Palmer J’s discussion of tikanga with his reasoning that tikanga is “law”.

Law in the common law tradition is assumed to be public, general, and knowable by all in advance (usually as a result of the law being reduced to writing). Furthermore, in the common law tradition (in theory at least) the same law is supposed to apply equally to everyone within the jurisdiction whether they be a prince or a pauper. Palmer J’s discussion confirms that each iwi and hapū creates, determines, and changes their own tikanga.

Many questions arise about tikanga – what it is, how it works, who it applies to, and how are people supposed to know how to do the right thing, in the right way, in accordance with tikanga? For example, does it apply to the law of contract formation between Māori? Is it a breach of tikanga for Māori to enforce a commercial judgment against other Māori in the common law courts? What source of regulation will ultimately apply to contracts between Māori parties and non-Māori parties? Some of these questions are examples of questions that may potentially arise in New Zealand given the direction in which the New Zealand courts are taking the law.